We’ve all heard that lies are stronger when they have traces of truth. Well, the same mindset applies to writing too. Readers get more immersed and grounded in stories that contain traces of what they already know. Consider Harry Potter: a world that JK Rowling imagined into our existing world.

When talking about imagination in writing, we have to give Rowling a lot of credit. The world she concocted sparks the imagination of all ages, multiple generations, and inspired some of the most popular tourist experiences in the world.

Let’s look at a few.

In the middle ages, the basilisk was described as a rooster with a snake’s tail. Another middle ages account describes a basilisk as a snake only nine inches long, yet extremely poisonous. All three descriptions are a far cry from Rowling’s overgrown serpent.

Ancient civilisations found the roots so humanoid that they began rumours, saying that the roots screamed when pulled from the ground. Some cultures even went so far as to say the cry of the mandrake root was fatal to living beings. Sound familiar?

Sirius

The star Sirius is considered the brightest star in the night sky. It can be found in the constellation Canis Major: meaning Great dog. In fact, Sirius is known as the “dog star.” Too cool, right? Considering Sirius Black can transform into a massive dog.

Bellatrix

Bellatrix is the third brightest star in the constellation of Orion. The name “Bellatrix” comes from Latin and means “female warrior” — a direct link to Rowling’s character, Bellatrix Lestrange.

Draco

Draco is, in fact, an entire constellation. Since ancient times, the constellation has been identified as a dragon. Aside from being a cool name, Draco Malfoy doesn’t seem to have any more ties to the constellation’s legends or mythology. Let me know if you think of any.

Along with those listed above, Rowling uses other celestial names including Andromeda, Cygnus, and Luna. Look them up!

I began writing Steel and Magic using made up names or researching popular medieval names. When I began adding my mythical creatures, however, I was inspired.

I have a Bachelor of Arts degree majoring in English. Throughout my studies, I was fascinated by medieval literature. The characters in medieval lore tug at my heart like old friends: Beowulf, Gawain, Morgana…

Realizing my affiliation, I began drawing on other passions of mine: classic tales including Gulliver’s Travels, ancient mythology…

Voila. After research and consideration, every named mythical creature in the Steel and Magic world is christened after some being from literature or mythology: breadcrumbs fellow English majors and history buffs would smile at.

Here are a few:

Gawain

Gawain is named after the protagonist from Gawain and the Green Knight — a 14th century medieval story. In Steel and Magic, Gawain is a tree sprite, described as a small willow with droopy boughs and beady black eyes. Where he gets his name from is the fact that he has green leaves, which reminded me of the Green Knight in the medieval tale.

Eldila

Eldila is named after C.S. Lewis’ beings who are related to both angels and demons. In my Steel and Magic series, there are good and bad spirits: seraphs and wraiths. Eldila, the water sprite Louie befriends, is named after these beings to connect her to both literature and the spirit realm.

Gulliver

Gulliver is many readers’ favourite sprite. As you can imagine, he’s named after Gulliver in Gulliver’s travels. Gulliver, the sprite, uses fire and wind magic to run faster than any other being. He travels fast, thus fitting the “Gulliver’s Travels” reference.

Aurae

Aurae is the primary wind sprite of the Steel and Magic series. She is named after Greek mythological creatures that were “nymphs of the breeze.”

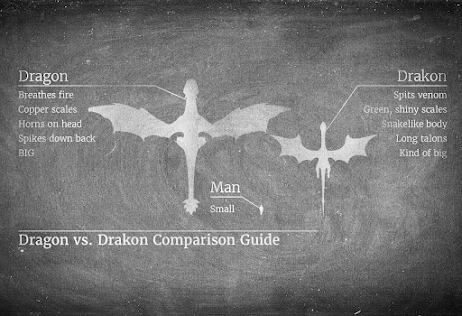

Dragons vs. Drakons

I’ve been asked why I’ve written both “dragons” and “drakons” into the Steel and Magic series. The main answer: they’re both in mythology and I wanted a good versus bad dynamic.

Dragons are self-explanatory — most of us have seen Game of Thrones, The Hobbit, Eragon… we know what dragons look like and can do.

Drakons, on the other hand, are myths older than dragons. They’re winged serpents and may spit venom, which perfectly describes these beasts in the Steel and Magic series.

Old English

What readers will find in book three, far more than books one or two, are many foreign words related to no language used today. These words are stolen straight out of an Old English dictionary. My university Medieval Literature teacher, who was an expert on the language, is among the few people who would catch the references without resorting to Google.

For example:

In this case, “ádumbian” refers to someone who is “mute or dumb.”

Also, whether I should admit it or not, I keep my Steel and Magic cuss words PG by resorting to old English swear words that are obsolete in today’s world.

All in all, adding pre-existing breadcrumbs and references into your writing can not only give you something to smile about, but a side quest for your readers too. Show off your researching prowess and your side interests by slipping obscure references into your work.

Yet, did she imagine it all herself? For the most part, yes. However, Rowling built on a lot of pre-existing concepts. In fact, many of these concepts actually ground her story to make it believable.

Let’s look at a few.

The basilisk

Originally, in Greek mythology, the basilisk was a north african serpent whose breath withered plants and killed whatever it touched.In the middle ages, the basilisk was described as a rooster with a snake’s tail. Another middle ages account describes a basilisk as a snake only nine inches long, yet extremely poisonous. All three descriptions are a far cry from Rowling’s overgrown serpent.

However, before the middle ages, Pliny the Elder — a Roman philosopher — describes the basilisk as a serpent of which “all who behold its eyes fall dead upon the spot.” This description is where Rowling garnered her inspiration for a giant snake that petrifies living beings.

The mandrake

Mentions of the mandrake plant can be found as far back as ancient Greek, Roman, and even biblical times. Throughout time, people have believed the mandrake to possess healing or even magical properties.The plant actually exists. It is known to have potent roots yet poisonous flowers. Where Rowling found inspiration for blotchy, screaming, infant mandrakes, however, is the fact that the mandrake’s roots resemble the form of a human.

Ancient civilisations found the roots so humanoid that they began rumours, saying that the roots screamed when pulled from the ground. Some cultures even went so far as to say the cry of the mandrake root was fatal to living beings. Sound familiar?

The names of the stars

One breadcrumb Rowling uses yet is rarely realised is her use of astronomical names as character names.Sirius

The star Sirius is considered the brightest star in the night sky. It can be found in the constellation Canis Major: meaning Great dog. In fact, Sirius is known as the “dog star.” Too cool, right? Considering Sirius Black can transform into a massive dog.

Bellatrix

Bellatrix is the third brightest star in the constellation of Orion. The name “Bellatrix” comes from Latin and means “female warrior” — a direct link to Rowling’s character, Bellatrix Lestrange.

Draco

Draco is, in fact, an entire constellation. Since ancient times, the constellation has been identified as a dragon. Aside from being a cool name, Draco Malfoy doesn’t seem to have any more ties to the constellation’s legends or mythology. Let me know if you think of any.

Along with those listed above, Rowling uses other celestial names including Andromeda, Cygnus, and Luna. Look them up!

Steel and Magic

If you’ve ever tried to write a story, you’ve probably heard the “write what you know” or “keep to your strengths” mantras.I began writing Steel and Magic using made up names or researching popular medieval names. When I began adding my mythical creatures, however, I was inspired.

I have a Bachelor of Arts degree majoring in English. Throughout my studies, I was fascinated by medieval literature. The characters in medieval lore tug at my heart like old friends: Beowulf, Gawain, Morgana…

Realizing my affiliation, I began drawing on other passions of mine: classic tales including Gulliver’s Travels, ancient mythology…

Voila. After research and consideration, every named mythical creature in the Steel and Magic world is christened after some being from literature or mythology: breadcrumbs fellow English majors and history buffs would smile at.

Here are a few:

Gawain

Gawain is named after the protagonist from Gawain and the Green Knight — a 14th century medieval story. In Steel and Magic, Gawain is a tree sprite, described as a small willow with droopy boughs and beady black eyes. Where he gets his name from is the fact that he has green leaves, which reminded me of the Green Knight in the medieval tale.

“Gawain shifted his lower body, stretched up onto the tips of his three roots, and walked onto the carpet toward them. The thin tendrils at the end of his stumpy legs flapped on the ground like elongated duck feet.”

- Elemental Links

Eldila

Eldila is named after C.S. Lewis’ beings who are related to both angels and demons. In my Steel and Magic series, there are good and bad spirits: seraphs and wraiths. Eldila, the water sprite Louie befriends, is named after these beings to connect her to both literature and the spirit realm.

Gulliver

Gulliver is many readers’ favourite sprite. As you can imagine, he’s named after Gulliver in Gulliver’s travels. Gulliver, the sprite, uses fire and wind magic to run faster than any other being. He travels fast, thus fitting the “Gulliver’s Travels” reference.

Aurae

Aurae is the primary wind sprite of the Steel and Magic series. She is named after Greek mythological creatures that were “nymphs of the breeze.”

Dragons vs. Drakons

I’ve been asked why I’ve written both “dragons” and “drakons” into the Steel and Magic series. The main answer: they’re both in mythology and I wanted a good versus bad dynamic.

Dragons are self-explanatory — most of us have seen Game of Thrones, The Hobbit, Eragon… we know what dragons look like and can do.

Drakons, on the other hand, are myths older than dragons. They’re winged serpents and may spit venom, which perfectly describes these beasts in the Steel and Magic series.

Old English

What readers will find in book three, far more than books one or two, are many foreign words related to no language used today. These words are stolen straight out of an Old English dictionary. My university Medieval Literature teacher, who was an expert on the language, is among the few people who would catch the references without resorting to Google.

For example:

“You ádumbian; so weak,” Asher scoffed.

“Ádumb—what?” Paul asked.

“Don’t answer,” Jake pointed at Asher. “I don’t want to know any of the names you’ve been yattering at me.”

- Eternal Bonds

Also, whether I should admit it or not, I keep my Steel and Magic cuss words PG by resorting to old English swear words that are obsolete in today’s world.

All in all, adding pre-existing breadcrumbs and references into your writing can not only give you something to smile about, but a side quest for your readers too. Show off your researching prowess and your side interests by slipping obscure references into your work.

Comments

Post a Comment